The general practitioner workforce: why the neglect must end

A new research report from the Australian Medical Association The general practitioner workforce: why the neglect must end has confirmed, after years of Government neglect, that Australia is facing a shortage of more than 10,600 GPs by 2031–32, with the supply of GPs not keeping pace with growing community demand.

Report summary

Health and healthcare are significant priorities for government and the public. Spending on health services and goods represents approximately 10 per cent ($202.5 billion in 2019–20) of Australia’s economic activity. This level of expenditure warrants continuous assessment of policy settings to ensure public expenditure on healthcare is achieving the best health outcomes possible for all Australians.

The continuing underinvestment and lack of reform in general practice increases overall health expenditure, reduces access and quality of healthcare, and widens the gap in poor health outcomes for vulnerable communities (e.g. people living in rural and remote locations, socio-economically disadvantage communities, and Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander people).

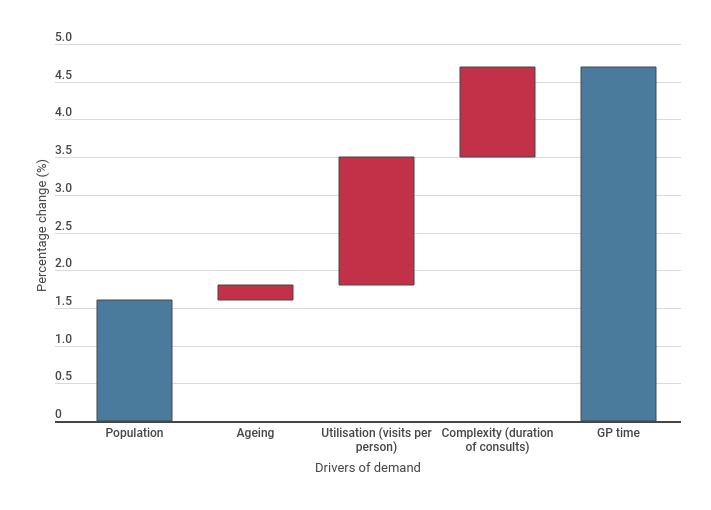

This research report provides a review of the contemporary literature and publicly available data to understand the role of general practice in primary care and profiles the current policy context to identify the opportunities for meaningful reform. The report also explores and quantifies the key drivers and outcomes in the variance between the demand and supply of the general practitioner (GP) workforce, to understand the scale of the GP workforce supply shortfall. The analysis demonstrates that the demand for GP services (measured by minutes of MBS items) has increased by approximately 10,200 GP full time equivalents (FTE) over the ten years from 2009 to 2019, resulting in total increase of 58.4 per cent or a compound annual growth rate of 4.7 per cent. The demand for GP services is driven by population growth (1.6 per cent), ageing (0.2 per cent), increase in number of visits per person (1.7 per cent) and complexity — increased duration of GP consults (1.2 per cent) (see Figure 1). The increase in the number of visits per person and complexity of GP services seen over the last decade is a response to the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases and comorbidities in the Australian population.

Figure 1: Annual growth in GP demand 2008–09 to 2018–19

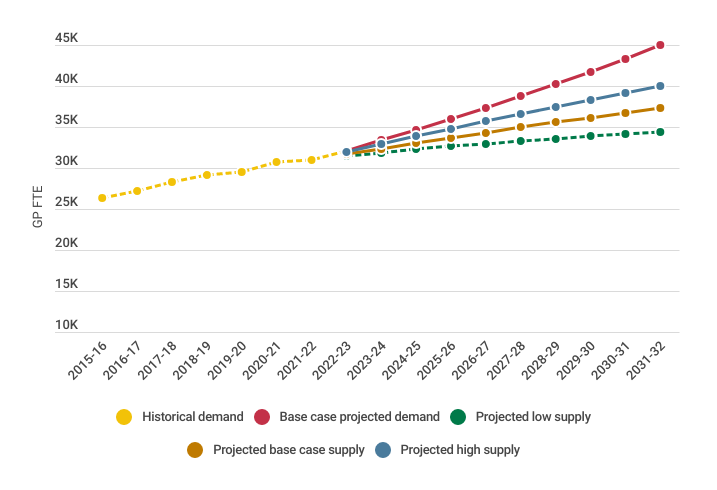

While demand for GP services has increased, the supply of services has not kept pace. This research report estimates that there will be an undersupply of around 10,600 GP FTEs by 2031–32, if GP training places continue to remain unfilled, and the rate of retirement and attrition from the profession escalates, which is not an unlikely scenario (Figure 2). Further modelling will be required however to estimate the number of Australian and overseas trained GPs required to meet the projected GP FTE shortfall over the next decade, to account for the increasing trend towards GPs working reduced hours due to socio-cultural and demographic changes among general practitioners. Western Australian Department of Health modelling in 2015–16 found that 2.1 Australian-trained general practitioners were required for every 1 Full Service Equivalent (FSE) of clinical practice.

Figure 2: Scenario modelling of GP workforce demand and supply projections

The projected considerable shortfall in GP supply has been reported to be due to underlying factors such as:

- negative perceptions and decreasing prestige of general practice among medical students

- limited opportunities to experience and gain skills in general practice in medical school and pre-vocational training which leads to a lack of interest in GP training programs

- general practice training not being prioritised in medical school over prerequisite prevocational training rotations such as paediatrics

- disparity in remuneration between GP registrars compared to their hospital counterparts and inadequate Medicare rebates for general practice (attributed to a lack of training and funding reform and years of no or low MBS indexation)

- ineffectual leave conditions for GP trainees

- inflexibility of general practice training.

Issues such as training employment conditions, the status and perception of general practice and remuneration through MBS funding arrangements must be addressed to have any chance of increasing the number of GP trainee applications and intake, while ensuring training and fellowship standards are maintained. A systems approach is required to resolve the significant GP workforce issues effectively and efficiently. Strategies to address the projected GP FTE shortfall therefore requires a focus on the full continuum of the GP workforce from first year medical education to prevocational, vocational training, and fellowship.

Evidence also suggests that GP-led team based primary care is the most effective model of primary care as it puts patients and continuity of care at the centre and enables all health professionals to practice to the top of their clinical scope. It also provides GPs with the time and capacity to undertake tasks that only they are trained to perform, such as diagnosis, treatment and overall medical management of the patient. The coordinated involvement of teams in patient care is an essential feature of high performing primary care.

In addition to the broader GP workforce issues, the rural general practice workforce requires additional and distinct solutions to overcome unique workforce issues such as professional isolation, uncompetitive remuneration compared to state hospital salaries and locum rates and the viability challenges of running a rural general practice. It is critical that state and Commonwealth governments work together to resolve the GP workforce issues, particularly in rural areas where public hospitals are under the jurisdiction of state governments. While it is outside the scope of this report to explore these issues in full, these concerns should be explored in further research and policy development.

Significant and necessary reforms which are identified in the Australian Medical Association’s (AMA) Delivering Better Care for Patients: the AMA 10-Year Framework for Primary Care Reform, the Commonwealth Government’s Australia’s Primary Healthcare 10 Year Plan 2022–2032, and the National Medical Workforce Strategy (NMWS), address the issues raised in this research report and include:

- support GPs to spend more time with patients and improve the indexation of Medicare to better reflect the rising costs of providing high-quality medical care and running a medical practice

- increase funding for after-hours GP care, wound care, and practice incentive payments

- address disparities in remuneration and employment conditions for GP registrars nationally

- increase exposure to general practice in medical school and prevocational medical training

- improve funding arrangements for GP services in aged care facilities

- increase funding for GP-led team-based primary care

- implement and adequately fund Voluntary Patient Enrolment to complement the MBS fee-for-service model

- implement reforms to improve access to medical care for regional/rural areas and disadvantaged communities

- support clear training pathways and solutions to rural medical workforce needs and distribution.

We are already seeing the impact of the shortfall in GP workforce supply, with growing inequities in healthcare access, poorer patient health outcomes, and increased expenditure on costly hospital services. Without immediate action this spiral will continue, and the sustainability of our healthcare system will be at risk. Reforms to address the cultural and systemic GP workforce issues have been identified by governments and key stakeholders and these now need to be funded and implemented in collaboration with the medical profession as a matter of priority.